Bennington Memorial Oak Grove

At 10:38 a.m. on July 21, 1905, the gunboat U.S.S. Bennington suffered one of the Navy’s worst peacetime disasters. She had arrived in San Diego, just two days earlier, after a difficult seventeen-day voyage from the Hawaiian Islands. Though both the ship and her men could have used a rest, they were soon ordered back to sea to assist the monitor U.S.S. Wyoming, which had broken down and needed a tow.

While steam was being raised, much of Bennington’s crew, having completing the hard and dirty job of coaling, were cleaning their ship and themselves. Below decks, an improperly closed steam line valve, oily feed water and a malfunctioning safety valve conspired to generate steam pressures far beyond the boilers’ tolerance. Suddenly, one of them exploded. Men and equipment were hurled into the air, living compartments and deck space filled with scalding steam, and the ship’s hull was opened to the sea. But for quick work by the tug Santa Fe, which beached Bennington in relatively shallow water, the gunboat would probably have sunk. As it was, she was so badly damaged as to be not worth repairing. Even worse, more than sixty of her crew had been killed outright or were so severely injured that they did not long survive.

The number of casualties overwhelmed the then-small city of San Diego’s hospitals, and badly burned Sailors had to be cared for in improvised facilities largely staffed by volunteers. Local morticians were hard pressed to prepare the Bennington’s dead for burial.

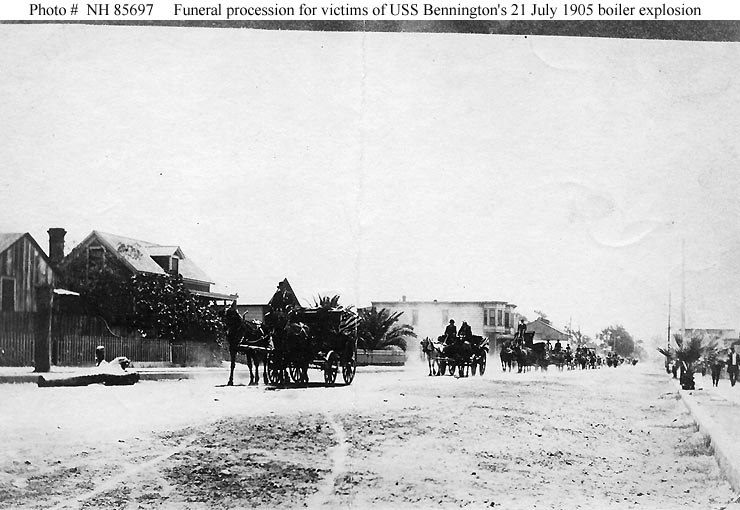

On the 23rd of July 1905, the day of the public funeral, there were 47 coffins. Officials didn’t have enough flags to drape the black-stained boxes, so the call went out for people to donate theirs. The caskets were loaded onto horse-drawn, flower-filled wagons.

It took four hours to make the trek from downtown, around the bay and up Point Loma to the Army’s burial ground at Fort Rosecrans located on the Point Loma heights overlooking the entrance to San Diego Harbor and what would, years later, become the North Island Naval Air Station.

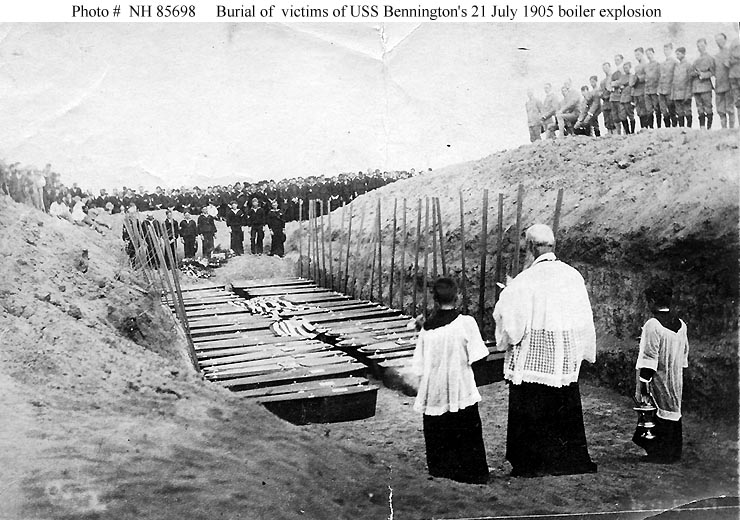

The papers called it a “desolate cemetery surrounded by a rude picket fence.” Hundreds of people joined the procession; the line stretched for more than a mile by the time the wagons reached the cemetery. A large crowd was waiting. They had taken boats five miles across the bay, then hiked some 500 feet up the cliff. “San Diego was in mourning yesterday,” the Union’s account said. The burial trench was 60 feet long and 14 feet wide. Surviving sailors from the Bennington, working in crews of six, unloaded the coffins and put them in the trench. It took them more than an hour.

Despite the awful death toll, which far exceeded that sustained by the Navy in the Spanish-American War, and sometimes-lurid rumors of misconduct on the part of some members of Bennington’s engineering force, official investigations concluded that the tragedy had not resulted from negligence. Eleven surviving crewmen were awarded the Medal of Honor for “extraordinary heroism displayed at the time of the explosion”. USS Bennington was raised, but remained inactive and unrepaired until sold in 1910.

The citizens of San Diego knew that there were many who had lost their lives and many that had sustained severe injuries that would eventually pass away in and in remembrance of the 65 sailors that died trees were planted. On Thanksgiving Day, November 30. 1905 70 California Live Oaks were put in the ground on the corner of Pershing Drive & 26th creating the Bennington Memorial Oak Grove.

Information credited to:

https://www.ibiblio.org

http://ussbennington.blogspot.com/2013_09_22_archive.html?m=1

59154total visits,9visits today

59154total visits,9visits today